- Shiny Thing$

- Posts

- The 1st Loser Runs the World.

The 1st Loser Runs the World.

SHINY THING$ #214: The Underbidder Theory

The Underbidder Theory

Rob Petrozzo, for Rally.

There’s a strange comfort in pretending prices are objective.

That the world finds comfort in concreteness, so we like to agree on what something “should” be worth. A house, a stock, a watch, a dinosaur bone. All of it needs a price. In all outcomes, the person who pays the most is the one who typically reveals the truth. High price equals high value, low price equals low demand. It’s a simple and rational formula.

Except it’s almost never true, and at best, its a trailing indicator that tells you what something “was” worth.

Behind every sale you’ve ever heard about - every record-breaker, every headline number, every “all-time high” that gets passed around on social media in tweets and Reels with the intent to entertain - there is someone you don’t see.

It’s the most important character in price discovery: The First Loser.

The one who showed up, raised their hand, and said with full conviction: I will pay almost that much.

This is the essence of “The Underbidder Theory” → The winning bidder sets the story, but the underbidder sets the price.

And in a world where assets, ideas, nostalgia, and attention are up for auction, the underbidder is more powerful than ever. This week on Rally, we take a look and the under-appreciated hero (and sometimes the villain) that really decides the price of everything…

Why the Loser Matters More than the Winner

Every market has a mythology around the winner. The person who had the conviction to put their money where their mouth is creates a narrative that gets amplified, because the winning number becomes the headline.

This past week, the original artwork for 'Star Wars: Episode IV' didn’t sell for “around $3M”… it sold for exactly $3.875 million, becoming the most expensive 'Star Wars' item ever sold. The people who follow the space repeated that exact number like scripture all week.

But look closer.

As bidding ascended, the outcome was left in the hands of two individuals. If the second-highest bidder had stopped $100K earlier or maybe even $1M earlier, the final price would be dramatically different. If they’d pushed one bid higher and done it quicker, that signal may have sent the eventual winner into an entirely different stratosphere of “I want this” and set off an entirely different course of action making that record sale dramatically bigger.

The winner doesn’t define the boundary of value. They only reveal how far someone else was willing to go.

The underbidder is the one who starts a fight.

They tell the world: There are at least two of us at this price.

That’s the real signal.

When there’s just one person willing to overpay, you get distortion.

When there are two, you get a market.

The Dangerous Game of the Two-Person Knife Fight

Some of the most bizarre prices in history came from exactly two people who refused to back down - the purest form of irrational competition disguised as valuation.

The most fascinating example of the last few years is one I’ve written about in the past, but is a more accurate example of low-liquidity public price-fighting than any other example you can drum up:

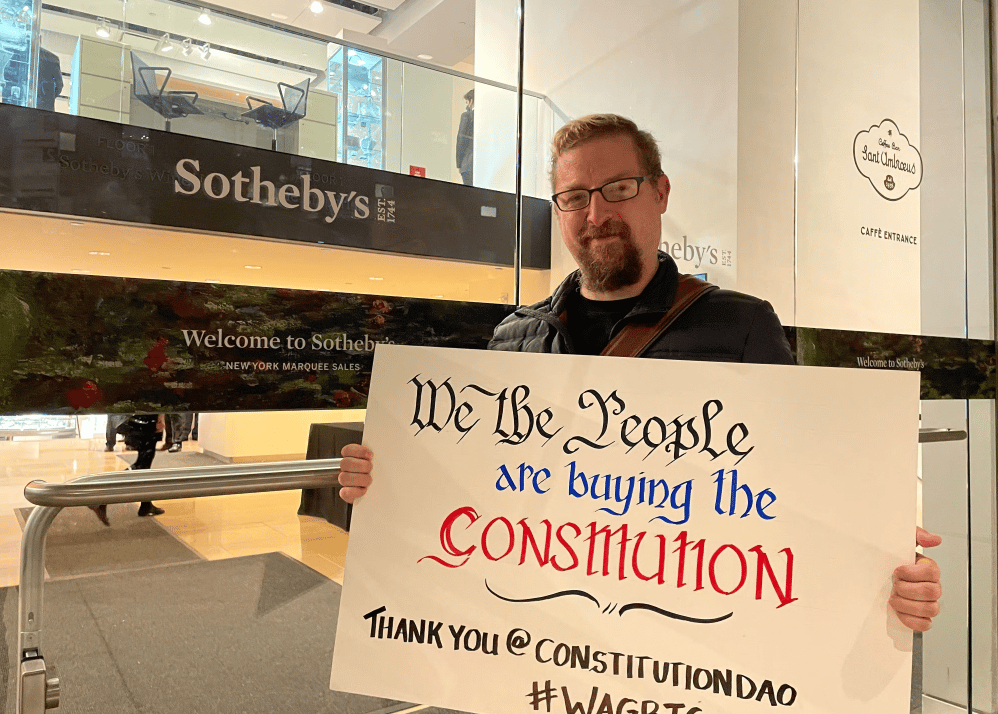

🔪 ConstitutionDAO vs. Ken Griffin, November 2021.

A group of crypto-natives raised over $47M from 17,000+ individuals in under a week to buy one of the few surviving copies of the U.S. Constitution. (PS, theres also one on Rally 😉). The DAO certainly didn’t need it because it had some clearly defined upside. They needed it because they collectively really wanted it.

Member and contributor to to ConstitutionDAO, Jeff Graber, who traveled to Sotheby’s HQ for the auction in 2021.

The potential for a faceless organization to bring a $47M war-chest to the auction was highly publicized leading up to the live auction. The fact that other deep pocketed billionaires might be waiting in the wings was also on everyone’s mind. Sitting in the middle of that drama was Sotheby’s own estimate of around $15M for the piece.

The bid instantly escalated into a theater-level showdown. Griffin, a billionaire used to winning, wasn’t about to lose to a swarm of low-budget strangers on the internet. And the swarm wasn’t about to be embarrassed in front of the world - especially considering this thing had gotten a little bigger than any of the founding members anticipated.

Both sides became irrationally committed.

This wasn’t price discovery. This was an old-school duel.

Griffin ultimately won the document for $43.2M - more than double what any experts believed the “real” FMV was. But that number wasn’t Griffin’s doing. It wasn’t the DAO’s doing. It was the invisible moment where the second-highest bidder said, “Yes, we’ll go that far” - in this case, a very public pool of capital controlled and governed by the individual from the DAO’s side that was voting “Yes” with each new bid.

The market didn’t actually agree the Constitution was worth $43.2M.

Two combatants agreed they were willing to go to war at $43.2 million.

The rest of us simply watched the smoke rise. I was one of those people who contributed - in my case, around $1,500 total - with no promise of any liquidity or ownership rights. I wanted to “us” to win, and did not care at all what the final price was and how it related to FMV.

The media hype died off shortly after the losing bid…

I got caught up in the underbidder conundrum, and helped reprice an asset that under normal liquid circumstances likely trades for a fraction of the outcome.

“The Morning After...”

This is where the Underbidder Theory becomes a lens rather than a story.

What happens when the deal is done and the dust settles?

Markets have a funny way of accepting the irrational as long as it’s public. A record is a record, and auction results don’t come with footnotes about emotional damage or pride. What inevitably happens is that big prices are “good” for all the players, and the downstream markets reorganize themselves around that new normal.

Even when everyone knows the price was a fluke, it becomes part of the valuation stack. It’s a data point as long as the object gets paid for, and it can’t be unseen.

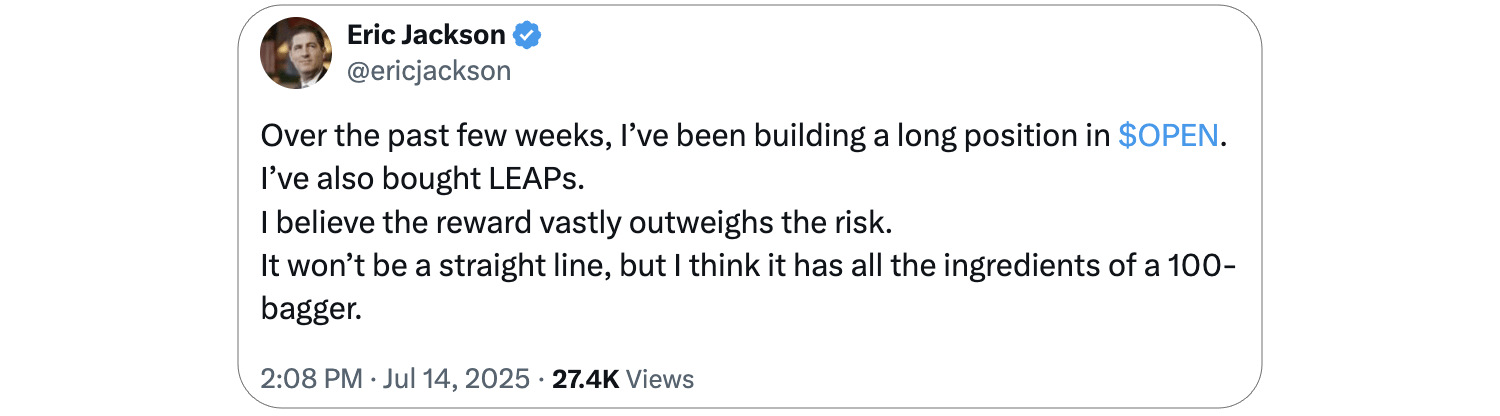

Stocks behave like this too. A thin float and two institutional buyers can drag a company’s valuation into orbit, and individuals who combine forces beneath an influential mouthpiece can create a brand new floor and a multi-year persistent bid driving a TON of liquidity and price action (Opendoor’s stock move led by activist investor Eric Jackson being the most relevant recent example).

Just like a rare comic book with only two serious collectors can triple in price overnight, or a piece of art can go berserk because two billionaires decide it would look great in their private museums, the public and private markets are both caught up in the fight-for-objects. The rest of the world, even those who quietly think the price is insane, recalibrates.

The “incorrect” price becomes a reference price and the “last trade” and reference prices are the building blocks of every chart, comp, and appraisal.

One irrational battle can define a decade.

The Math: Two Bidder price action vs. Many Bidders

A two-person auction is like watching two sumo wrestlers collide in the center of a ring at times. The entire landscape can change from one impulse - in the auction example, one final raised hand.

👇 What happens with just two bidders👇 :

→ Volatility explodes. Prices can overshoot in either direction because liquidity collapses into a duel.

→ Narrative becomes outsized. The winner isn’t just buying the asset, they’re buying the story of beating someone equally obsessed.

→ The underbidder gains mythological significance. They become the unseen force that dragged the sale into the stratosphere.

Two bidders do not make a market, but they did make a moment, and often times, a new comp.

👇 Now, the other side👇 :

If hundreds or thousands of people want something - a PlayStation 5 at launch, a sneaker drop, a meme coin, a pair of game-worn sneakers - the underbidder is no longer a single person. It becomes a layer of demand. For context, this is what we’ve always strived for at Rally, as out thought was that thousands of individuals who have a real connection to an object are better at pricing that object than two wealthy individuals who refuse to lose.

In these cases:

→ Prices become more efficient as its less determined by ego, and more by consensus.

→ The gap between the winning bid and next bids becomes small. You don’t get runaway insanity because too many people are setting boundaries, and the spreads stay tighter.

→ The underbidder becomes the crowd. Crowds anchor value much more effectively than individuals.

These are the markets that lead to durable reference prices.

Not the duels. They’re stampedes.

What it all Means for Price Transparency

If the underbidder is the true mechanism of price, then the future of markets isn’t about who wins. It’s about who almost wins.

Collectibles, crypto, RWAs, stocks, and everything else is drifting toward a world where the layers of demand beneath the winner matter more than the winner themselves:

→ Depth of bids

→ Distribution of interest

→ Number of qualified buyers

→ Spread between top and bottom bids

→ How fast demand appears or disappears

These metrics are becoming the new FMV. It’s no longer the last trade or the headline number.

It’s the shape of the demand curve underneath it.

We’re entering a world where transparent underbidding will define how people justify what something is worth, especially in categories where liquidity is thin and narratives travel faster than math.

Imagine a future where:

→ You can see the top 50 bids for an illiquid asset that isn't even officially for sale.

→ You can see every unique failed bid for a dinosaur fossil along with the pre-auction sales book.

→ You know exactly how many investors strongly considered deploying cash to an IPO and the reasoning behind the absence of their bid.

→ You can track transparency not just around prices, but around pressure.

FMV becomes less of a number and more of a topology chart, and suddenly, valuation stops being a guessing game and becomes a science that incorporates human behavior.

We’re living in a moment where everything is getting priced, so the reset is necessary. It’s not just assets… but nostalgia, scarcity, identity, participation, and belonging thats getting a value. People want to know: How do I make sure I’m not overpaying for something? How do I know the price reflects reality, not ego?

The answer is to stop obsessing over who won, and start asking who almost won. Who had the real intent to deploy real capital?

The underbidder is the skeleton key of valuation. They tell the truth the winner can’t because the winner’s job is to justify the number, not reveal the market.

Whenever you’re looking at a price, whether its a sale, an IPO, a last trade, or an auction result, you have ask one question:

Was this number built on a crowd or a duel?

If it was a duel, take a breath and a quick step back before making a decision. If it was a crowd, you’re looking at something real.

Either way, the loser already told you the truth.

Until Next Week…