- Shiny Thing$

- Posts

- ✨$T 0211: The Inside Isn’t Always “Better.”

✨$T 0211: The Inside Isn’t Always “Better.”

Access, ego, and the road back to real scarcity.

This Week: The Private Market Mirage, and the illusion of “getting in”…

There’s a new kind of ambient FOMO circulating in tech and retail finance right now, and even those who don’t fully understand the mechanics of it are interested. It’s the idea that regular people are finally getting access to the private markets - that the moat around the companies of tomorrow (before they IPO and go public on the stock market) has eroded just enough for retail to squeak in.

If you’re anywhere near finance, gambling, or markets-adjacent, your algo has probably serving you more and more ads inviting you to invest in companies like SpaceX, OpenAI, Anthropic, and whatever the next generation-defining company might be - companies that re still privately held, but are considered the mulit-trillion dollar opportunities.

It feels like the velvet rope has finally lifted. The dream has always been that retail could one day play on the same field as the big banks, the ultra high-net-worth family offices, and the preferred clients who get the allocations at Series C, D, E, and Pre-IPO.

But, it’s never that easy.

Theres been this overwhelming feeling of “Am I actually the sucker?” As much as I’ve personally wanted to believe I’m special and important in the landscape of tech and finance, I’ve had that feeling personally ever since my first [very small] angel investment in 2019 (which quickly went to zero - a story for another newsletter).

What it kinda comes down to is that most of what’s being sold to retail right now isn’t actually stock in these companies. They’re derivatives, synthetic exposure, SPVs, and sidecar vehicles with fees built into fees built into fees. And often the prices you pay and the prices those units of ownership trade at are not in any way tracking the underlying business at all. In some cases, the thing you’re buying is multiple layers of abstraction removed from the real equity. You’re not on a cap table. You’re actually not even in the room.

While it’s definitely an important step in bringing retail into the fold, the potential long term issue as I see it is that the trend is being celebrated under the banner of access. While some companies and brokerages are truly making it happen, many are just pushing out product to ride the wave.

“Everyone can invest now,” they say. “This is the democratization of private markets.”

Yet more often than not, these products rely on opacity. They rely on the hope that you’ll accept the word “private” as a stand-in for “premium,” and that you won’t ask the real question that we explore in this week’s edition of Shiny Thing$:

If this is so good, why are they giving it to me?

→ Private Clubs & The Psychology of “Being Early”

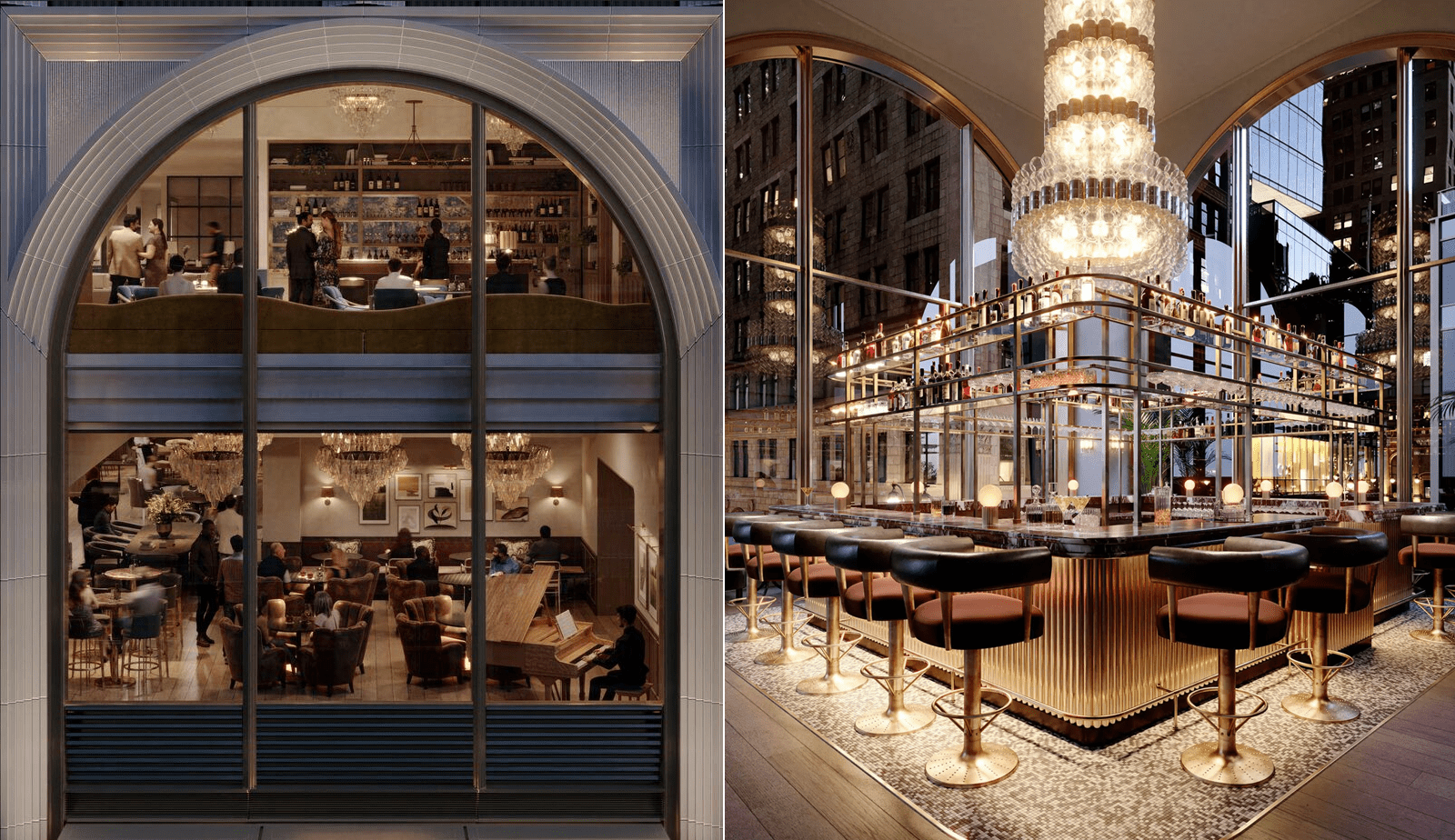

The Corner Store (left) and the nondescript guarded entrance of sister restaurant The EightySix (right), the two hardest reservations in NY currently. The only realistic method of securing a reservation to the former requires a $5,000 membership tier on reservation app Dorsia, and The Eighty Six is currently not accepting reservations.

I speak to a lot of things in the context of New York City, but the current state of extremes we’ve been witnessing here for the better part of the last 2 years is a parallel to false-scarcity mindset we’re seeing in private market investing. Walk around the city right now and you’ll see a new wave of lines outside impossible-to-get-into restaurants and new private members clubs - beautifully designed rooms that smell like pine and money and a little bit of desperation. The waitlists for everything are long. The menu prices and entry fees are absurd. And the promise is always the same: Get in, because most people can’t.

But here’s the thing no one wants to admit but everyone already knows:

Most of these spaces aren’t providing real value. They’re providing validation.

The allure of “private” has nothing to do with utility. It’s about the ego-hit of being on the inside. Paying for the right to say: I got in and you didn’t.

And that psychology maps perfectly onto private market investing, especially considering that over time, the exclusivity inevitably needs to loosen up and more of those “dreamers” sneak in (a very delicate balance that Soho House, the pioneer of private members club, learned there hard way as a publicly traded company).

The 19th private members club to open in NYC over the last 4.5 years, “Moss” - a 4 level dining, entertaining, and wellness space just south of Times Square, with a $3,950 initiation fee and $745 monthly dues.

When something is labeled “exclusive,” the flaws becomes forgivable. No pool at the new private club? All good - the status makes up for it. A company like Figma doing $300M in revenue but getting priced at a $20B IPO, then shooting to nearly $70B right out of the gate? Still fine, because if your allocation came at a $10B valuation, you’re too busy feeling early and rich to worry about the math. Meanwhile, the retail allocation (the shiny new feature on basically every retail trading app) was so tiny that most brokerages could only hand out one share per person at the $33 per share IPO allocation price. And yet people still posted screenshots on X. It wasn’t financial exposure; it was social proof.

Figma down nearly 70% since its IPO. How long can that illusion of “you’re in” last when many of those same retail participants are now underwater?

We’ve built an ecosystem that encourages people to squint past reality because the words private and early act like a fog machine. They soften the edges that your brain knows will cut you later, but your heart refuses to acknowledge.

They let you believe you’re buying more than just an overpriced membership. You’re buying proximity to greatness. To the billionaire class. To the chosen few.

But proximity isn’t ownership, and exclusivity isn’t alpha.

The inside isn’t always “better.”

Sometimes it’s just more expensive.

→ The Banks, The Allocations, and the Last Real Arbitrage

Before the private market shares were available to retail investors: the May 2019 Uber IPO, where wealthy Goldman Sachs private wealth clients cleared over $1B from their allocation.

For decades, the only people consistently making money in the private markets were the ones who controlled the gates: the Banks (Big B).

They were the ones getting the allocations in the rounds before the rounds. The whispered offers and preferred shares with the preferential rights went to them, and they were the ones who captured most of the upside long before retail even knew a company existed.

Take any high-profile IPO over the last 20 years and look at the spread between where the banks’ clients got in and where the stock opened on day one.

A simple real-world example, condensed:

The Airbnb IPO (2020)

Priced at $68

Opened at $146

A 115% day-one jump

That delta - the distance between “what insiders paid” and “what retail paid on day one” - is where the real money was made. Billions created in the blink of an eye, all before the public ever got involved.

And that is precisely why banks have resisted true democratization.

Private markets have been their most reliable profit engine for decades.

So why the F*CK would they want you peeing in their pool?

They don’t - because in their eyes, retail doesn’t add value. Retail adds volatility. Retail adds complexity. Retail takes the last slice of the pie after everyone else has eaten. Retail asks lots of questions and annoys the system.

The private equity products retail is being offered today often exist because the banks already got what they wanted. They made their money on the actual shares. Now they’re selling the leftovers: the rights, the wrappers, and the “access products” built to mimic proximity without granting their same level of participation.

If you’re getting invited now and feel like you hit lotto, it’s not because the world is opening.

It’s because the insiders are probably done, or they couldn’t fight it anymore.

So which one is it?

→ Tokenization & The Return to Reality

Robinhood’s “To Catch a Token” event in the south of France, where CEO Vlad Tenev announced tokenized private company shares were coming to the app. Seen on the right in the intro clip, Tenev arrived in a 1961 Jaguar E-Type, wearing a vintage gold GMT Rolex - both of which are current Rally portfolio assets.

This is where tokenization sits in an interesting crossroads.

Used correctly, tokenization can give retail access to actual ownership, not synthetics. Done wrong, it just becomes another abstraction layer - a digital version of the same opaque private market products that already exist, dressed in a blockchain costume.

But the real frontier is a bit different. it’s the idea of bringing assets that exist in the physical world with real scarcity, real provenance, and real history, onto rails that increase liquidity without diluting the asset itself.

You know this well because we deal in these assets every day.

A dinosaur fossil.

A PSA-10 Pokémon set.

A Birkin prototype.

A historically significant watch.

A Kobe jersey that touched greatness.

The value isn’t hidden in a spreadsheet. It doesn’t rely on a future IPO or a new valuation memo. It doesn’t require storytelling gymnastics to justify a 100x multiple. It is what it is and is going to be what it’s going to be.

It exists right now.

You can point at it and you can contextualize it in culture.

Tokenization has the potential to make these assets tradeable without making them less scarce, and that’s where the entire private market conversation starts to shift.

Because once everything “private” becomes tokenized and accessible, the illusion of private disappears. When that myth of exclusivity gets punctured, the scarcity theater collapses.

→ When “Private” Becomes Public, Scarcity Becomes King

The inevitable endgame is simple:

The ego-boost of private markets will degrade the same way commission fees did.

Once one platform opens the gates, the next one has to widen them. The next platform then offers more access, and competitors have to lower the bar. Once retail gets one share of a hot deal, they’ll demand more, and when access becomes ubiquitous, “private” becomes meaningless.

It’s a race to zero, and we’ve already seen this movie:

Zero-commission trading

Zero-minimums investing

Zero roadblocks for non-accredited investors

Zero barriers between new investors and the same products the wealthy have always had

We did it at Rally, and we built a product on that last point, so we’ve certainly been a beneficiary of it. The private markets are on the same trajectory now.

And when the exclusivity evaporates, our take I that all that will remain is real substance. Actual, provable scarcity.

Because the truth is, the only thing that survives “democratization” is the thing that can’t be replicated once the doors open.

Everything else becomes a commodity.

What’s left, and what’s real, is scarcity with provenance.

Assets that don’t need to pretend to be scarce, because they are.

That’s the world we’re building toward here at Rally and beyond.

And ironically, it’s far more “private” than the private markets have ever been.

Until next week…